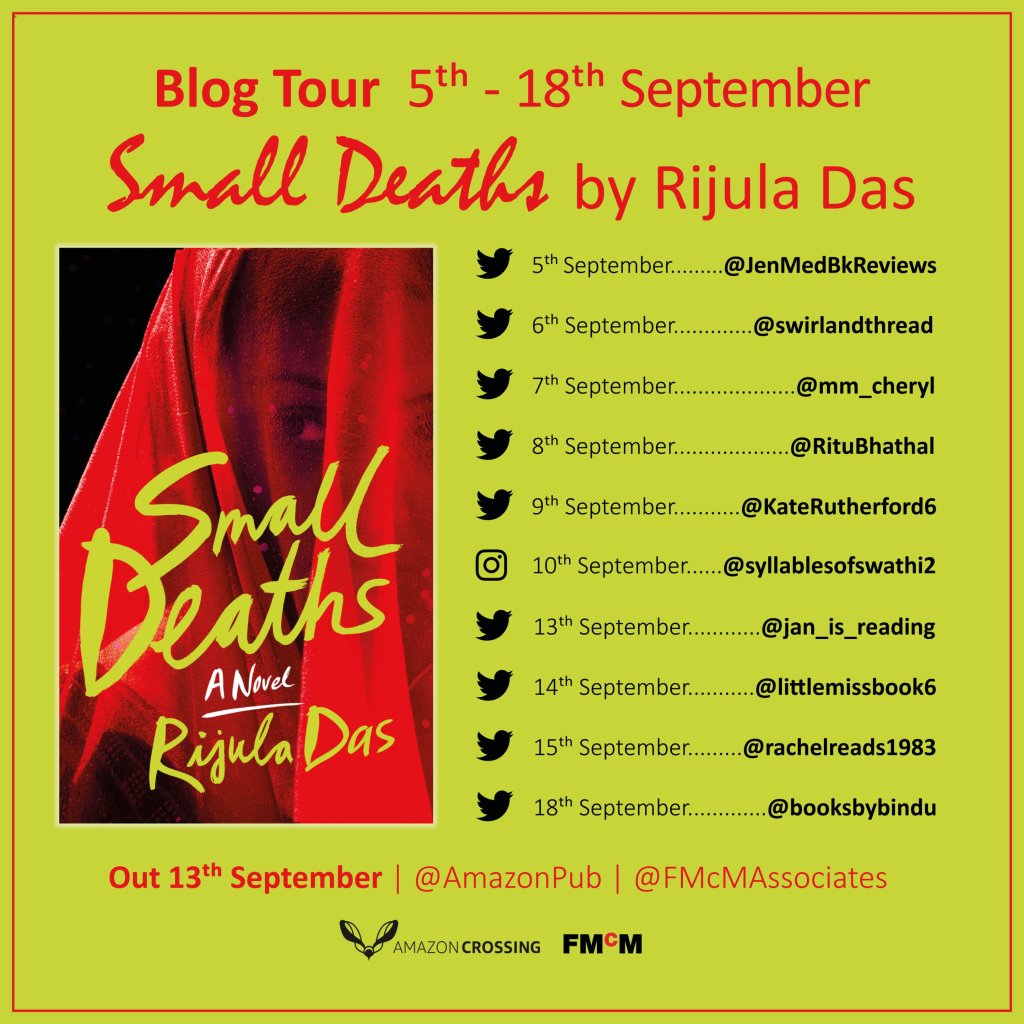

I am delighted to be a part of the book tour for the release of this translated title, Small By Rijula Das, published by Amazon Crossing.

In the red-light district of Shonagachhi, Lalee dreams of trading a life of

penury and violence for one of relative luxury as a better-paid ‘escort’.

Her long-standing client, Trilokeshwar ‘Tilu’ Shau is an erotic novelist

hopelessly in love with her.

When a young girl who lives next door to Lalee gets brutally murdered, a spiral

of deceit and crime begins to disturb the fragile stability of this underworld’s

existence. One day, without notice, Lalee’s employer and landlady, the

formidable Shefali Madam, decrees that she must now service wealthier

clients at plush venues outside the familiar walls of the brothel. But the new

job is fraught with unknown hazards and drives Lalee into a nefarious web of

prostitution, pimps, sex rings, cults and unimaginable secrets that endanger

her life and that of numerous women like her.

As the local Sex Workers’ Collective’s protests against government and police

inaction and calls for justice for the deceased girl gain fervour, Tilu Shau must

embark on a life-altering misadventure to ensure Lalee does not meet a

similarly savage fate.

Winner of the 2021 Tata Literature Live! First Book Award – Fiction

Longlisted for The JCB Prize for Literature 2021

SMALL DEATHS

Rijula Das

Set in Calcutta’s most fabled neighbourhood, Small Deaths is a literary noir

as absorbing as it is heart-wrenching, holding within it an unforgettable

story of our society’s outcasts and marking the arrival of a riveting new

writer.

My Review

Small Deaths by Rijula Das

I was intrigued by this book after reading the blurb I was sent.

A book centred around the oldest profession in time, set in the town of Shonagachhi, Calcutta, in India.

We start by getting to know Tilu, an aspiring author of erotica who wants to get better recognition for more literary work. He visits the Blue Lotus in Shonagachhi whenever he can afford it to meet Lalee, his favourite concubine.

A visit there ends with the other inhabitants of the house finding the body of one of the girls who lives among them.

What follows is a tale of true sadness. These women don’t choose to be dragged into prostitution; however, once there, they are estranged from their loved ones due to the shame of the work they have been made to do. The other girls become their families. But nothing can stop the way society taints them and how they are looked upon as public property; the johns do whatever they want, and the madams who are there to ‘look after’ them are just as bad, selling them from one bad situation to another, and not often a better one.

Here, an awful sex trafficking ring is exposed, involving a much-respected ‘holy’ man. But the violence that is used toward women is horrific.

It made for uncomfortable reading, in some ways, but the sad truth is that these things do happen the world over; it’s just that we aren’t all privy to the knowledge.

We see the story unfold through several viewpoints, including the above two characters, other girls from the Blue Lotus, police officers, a pimp, and some other random characters, which can be a little confusing but adds another layer to the story.

An interesting but heartrending read.

About the Author

Rijula Das received her PhD in Creative Writing/prose-fiction in 2017 from

Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, where she taught writing

for two years. She is a recipient of the 2019 Michael King Writers Centre

Residency in Auckland and the 2016 Dastaan Award for her short story

Notes From A Passing. Her short story, The Grave of The Heart Eater, was

longlisted for the Commonwealth Short Story Prize in 2019. Her short

fiction and translations have appeared in Newsroom, New Zealand and

The Hindu. She lives and works in Wellington, New Zealand.

Author Q & A

Tell us a little bit about your book, Small Deaths?

Set entirely in the Calcutta’s red light district, Small Deaths is the story of Lalee, a sex worker trafficked into the trade as

a child who dreams of trading her precarious life for that of a better-paid escort. Tilu Shau, her loyal client, makes a living

writing cheap erotica and dreams of literary fame and Lalee’s love. When a young woman is murdered in Lalee’s brothel,

the two of them are drawn into a misadventure that threatens the fragile stability of their lives and forces them to ask

what is the price of one’s right to dignity, a future and a life?

The book was originally published as A Death in Shonagachhi – what role does the setting of Shonagachhi play in your novel?

Sonagachi is a neighbourhood in North Kolkata, and the largest red-light district in Asia with several hundred multi-storey

brothels where more than 30,000 commercial sex workers live and work. It is rare to find works of fiction set entirely in

this area, even though the neighbourhood is one of Calcutta’s oldest. The novel is a product of my doctoral research on

the relationship between sexual violence on women in India and public space; I looked at how we ‘allow’ women to access

public spaces, and what punishments are meted out to them when they violate the unwritten rules. The red light district

in traditional, patriarchal societies is a space of contradictions. They are often the oldest of neighbourhood, well-known

and yet, unacknowledged spaces. I wanted to understand the way sex workers access a city where they are invisible

citizens –– how they live, die, advocate, organise and make a life that is uniquely their own.

Why was it important to you to tell this story now?

Living in the world we do, it is easy to forget that women’s rights are not actually indelible and unalienable. It is easy to be

lulled into a sense of security. But women’s rights, or indeed the rights of vulnerable people, irrespective of gender identity

is under siege at all times, many instances of which we are witnessing at present time. The right to bodily autonomy is an

unfinished fight for us, as is the constant fight for the recognition and acknowledgement of women’s labour, wherever

that may take place. Stories from the margins like that of women like Lalee, because they are real, living women, are a

useful and timely reminder of where we are and how easy it is to deny human rights to vulnerable people even in this age.

How do you do your research? Your research specifically looks at the connections between public space and sexual

violence – how did this inform your writing of Small Deaths?

There is a wealth of both academic research and case studies and interviews with the sex workers of Shonagachhi. Social

welfare organisations are extremely active in the area and have extensive grassroots knowledge. As I wrote Small Deaths

over 7 years, the research seeped into the work, informing the fictional narrative, and sometimes changing or adding to

the course of events. In creative work research informs the lived experience of the book’s universe, but it should never

get in the way of the narrative. It’s often a tight-rope walk.

Tell us more about writing truthfully about sexual violence and why it was important to write on this theme?

We’ve always written about sexual violence, but how we do it, matters. What we decide to show and what we decide to

leave unsaid, matters. Very often we see gratuitous, even erotic portrayal of sexual violence in fiction. As someone who

has faced sexual and other forms of violence as a woman, it changes the way I could write about it. I had to ask –– at what

point does writing a sexual violence scene become voyeurism? How do I write with authenticity, empathy and truth and

still reserve dignity for those on whom the violence occurs? Whose eyes and heart does the chapter look through, is it the

victim or the abuser? There are certain expectations when a book deals with the life of women trafficked into sex-work,

but the greatest satisfaction, for me, came in subverting any pandering to trauma-porn, or a representation of abject and

unabated victimhood because that is not consistent with the reality of life on the margins.

Were there news stories that particularly inspired your work?

Small Deaths is inspired by real people and real events, and where reality is shocking, invention is not only unnecessary

but a travesty. I wanted the book to cleave as close to reality as possible and as such, a number of real events have inspired

the action in the book. The scandal of an ashram called Dera Sacha Sauda where a powerful, self-styled guru held women

hostage in a warren of rooms and sexually abused them for years has inspired events in the book. The disappearances and

deaths of sex workers, and the migration of women across international borders for sex work in coercive circumstances

have inspired both characters and events. It is however not one event, but a landscape and an ecosystem developed over

decades that this story has grown from.

Are there any books that you would recommend to explore more about the themes in your novel?

There are a number of academic works that I read and referred to while writing this book. Fictional work set entirely in

Shonagachhi is harder to come by.

You have translated a number of books in your work, including Nabarun Bhattacharya’s short fiction. How do you

think your translation work helps to inform your writing?

Translation has definitely influenced how I use language. How we use English as Indian writers is evolving as our relationship

with English becomes more organic, more intertwined with our multilinguality. Reading in diverse literary traditions, as

translation helps us do, also changes my relationship with narrative form and storytelling.

What made you want to become a writer? Why fiction?

I’m not sure we decide to become a writer any more than we decide to become ourselves. It does take a certain amount

of practice, showing up for it over decades, a lot of hard work without any promise of reward or even the assurance that

one should persevere, but we write because there is no other way to exist. Fiction allows me, personally, the necessary

distance from myself to explore places that would feel too exposing to do as autobiography. It is also the sheer joy of

being in other people’s heads, creating characters who are entirely different from me, and watching them take-off on

their adventures.

Which other writers have informed your work?

It is hard to see my own influences. I often read people whose work I enjoy as a reader but as a writer, we’d be widely

different. I’m a big Terry Pratchett fan. His comedic brilliance and timing is so effective and subtle that you almost don’t

realise the sheer genius required to pull it off. Jeanette Wintersen, Marguerite Duras and Borges have been abiding

influences.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers?

To stick with it. People often think of talent as the sole variable that makes a writer, and while there is such a thing,

another very important variable is the ability to stay the course. It takes time to make even a bad book, a good one can

and does take time to see the light of day.

What’s next for you?

I’m finishing a translation of Nabarun Bhattacharya’s novel, soon to be published by Seagull Books. After that I hope to

focus on my second novel.